The Heart Understands Without Words

by Jenny Clendenen

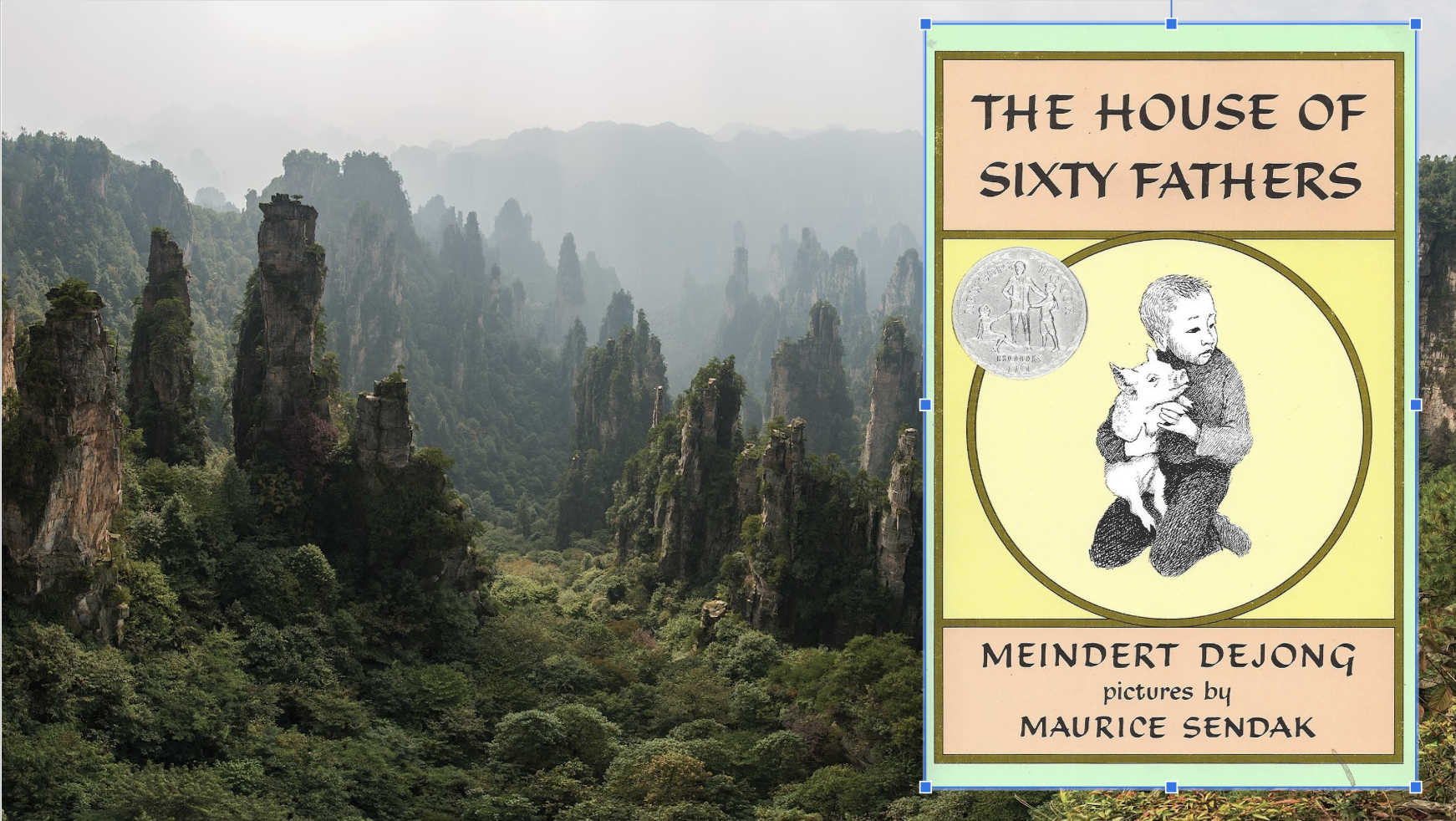

The House of Sixty Fathers (1956) by Meindert DeJong is a story that will draw you in slowly. You'll wade through the incessant rain of the opening, between the repetitions of "drops" and "drips," and see the bullethole in the sampan that says you're in wartime China. You'll see little Tien Pao's pig and ducklings' reactions to the rain, and his reaction to their reactions to the rain. The swaying and bobbing of the boat, and the drifting voices and drumming rain, will almost make you yawn. It's the exact opposite of exciting. It's monotonous, like a single memory that won't leave you alone.

At the bottom of page two, you'll slip into Tien Pao's own dreamy memory of his family's recent flight from the ruins of their village, which the Japanese have just invaded and burned, and you'll realize you've been set up. That the syntax and diction and substance of the opening have led you, unwitting and perhaps slightly bored, to the slaughter.

From the third page to the last, you'll sit up and take notice of these innocent paragraphs that sound so simple and slow, but are tight-packed with premonitory language and layers of tension.

And you'll be glad you stayed with it, because right around the corner, in Chapter Two, you'll be swept away with Tien Pao and his pig, alone in the sampan, by a river of page-flipping, heart-wrenching, high-impact drama—right back to the brutally occupied region of his ruined village.

You'll wonder that this is a children's book—and it almost wasn't. But if you stick with it, you'll understand why it's good for kids, though it's best to read it with or to them. as there's much to talk about. History, of course, and the horrors of war, but also forgiveness, and most importantly, the feelings that cross cultures, language, eras, and more.

The House of Sixty Fathers is about little lost Tien Pao's quest to get back to his family, to find shelter and food as he journeys with his pig through dangerous mountains. Not only must he evade enemy soldiers, but his own people too, who are starving and would eat his dear pig. Then he saves a fallen American pilot, and his journey takes a powerful turn.

That quest and those situations alone make for a story tight with tension; but it's Tien Pao's compassionate heart that makes us buy in: his selfless gift to a starving child; his salvation of the pilot despite the risk to himself; his fierce protection of his pig. So many more kindnesses to and from strangers, and especially, to our relief, from an entire barracks of sixty American soldiers, for what goes around does come around.

If I were to summarize those acts of kindness here, they'd sound trite—but I promise you, in Meindert DeJong's hands, they're so credible you're bound to choke up. It's been many years since a book made me cry, not in grief but in the warmth of seeing one person intuitively knowing what another one needs, and gently providing it. As Tien Pao thinks when the fallen airman and he communicate using charades, "the heart understands without words."

That's's the perfect line to repeat at the very end, after one of the most masterful, beautiful scenes ever written. I sobbed as I read the last few pages. Not cried. Sobbed. I don't want to spoil the ending for you, but trust me, you'll be glad you finished the book—and you'll never forget it.

The House of Sixty Fathers is heart-wrenching, but somehow still gentle and thoughtful, because of the childlike language and perspective. There's no emotional manipulation going on; the author's written words create scenes that flow like an unforgettable film, the scenes and the history speaking for themselves. We feel what we feel because we're seeing what's truly real.

It was all the more real for Meindert DeJong, who was a historian with the Fourteenth Air Force (the Flying Tigers) near Hunan. He and his unit had befriended a lost, orphaned boy who chose him as his special "father." DeJong wanted to adopt him after the war, but the rise of Communism in China intervened, and they never saw each other again. DeJong never had any children, except on the page; Tien Pao was his little boy.

I think that explains the depth and beauty of this book. There's extra depth and beauty for me, for personal reasons. The heart does understand without words.

We welcome your comments and questions! And if you'd like ideas for teaching this great book to kids, and for bringing its lessons to life in hands-on ways, see our Creative Teaching Resources for The House of Sixty Fathers.