The Narrative Arc

The narrative arc is a critical concept for understanding the structure of a book, whether kids are reading one or writing one. In our experiential workshops, we always begin our "field trip " through a story by explaining the concept of the arc, then talking and playing our way through its six sections.

We're often asked how we explain the narrative arc to kids. We'll share that with you here, along with explanations and examples of each section of the narrative arc.

Explaining the concept

1. Define the words. Explain that a narrative is a story, and that an arc is a curve (not a giant boat). The curve of the story comes from the rise and fall of the story's action.

2. Define the narrative arc as the action chart for a well-written novel.

3. Explain how it's made. If you were to graph the intensity of a story's action on a chart from beginning to end, and then draw a line from point to point, you would see that the action level rises and falls in an arc. (You might want to point out that this is the arc of every well-told story, whether it's a ten-second ad, a Homerian epic, or an anecdote about your day. For instance, when you tell a friend about losing and finding something important, you naturally follow the narrative arc. You don't start with the most exciting part; you work up to it, and then wrap up with the relief and a lesson learned. "While I was brushing my teeth . . . I suddenly realized . . . I tried . . . I looked . . . I called . . . Then I remembered . . . Whew! Next time I'll . . .")

4. Show what it looks like. In classic children’s literature, the action is divided into six parts in the same order. Point out that the arc begins low, rises high, then drops down and stops—but stops higher than where it began.

5. Explain how it's used. The arc is used by authors to write, and by students to analyze.

Authors follow the arc to make sure the story stays interesting while the character grows and the message gets across. In fact, the very purpose of the action is to provide interesting ways to

reveal a protagonist's problems

provide opportunities for growth

show proof of success

Students use the arc to study how the author did that, section by section.

6. Explain why it's important. The narrative arc is more than a writer's and reader's tool. As the action steps up, the protagonist steps up, so that by the end s/he's learned coping skills and conquered flaws, and has clearly changed for the better. The arc becomes

the story's action chart,

the character's growth chart, and

and the reader's formula for gaining life skills and self-esteem

When we understand what the arc is and does, and why it matters, we become better writers. We also become more astute readers and students. And when we see how to how to teach or learn the same lesson the character learned, we become better people.

Ways to proceed

In our workshops, once we've explained the concept, we start working our way through the book's plot, defining each part of the arc as we come to it, and summarizing the scenes and events that fit there. And, of course, pausing to DO WHAT THE CHARACTERS DID! Because that's what we're all about!

You can do it that way if it suits your plan, or you can just continue with the section explanations below.

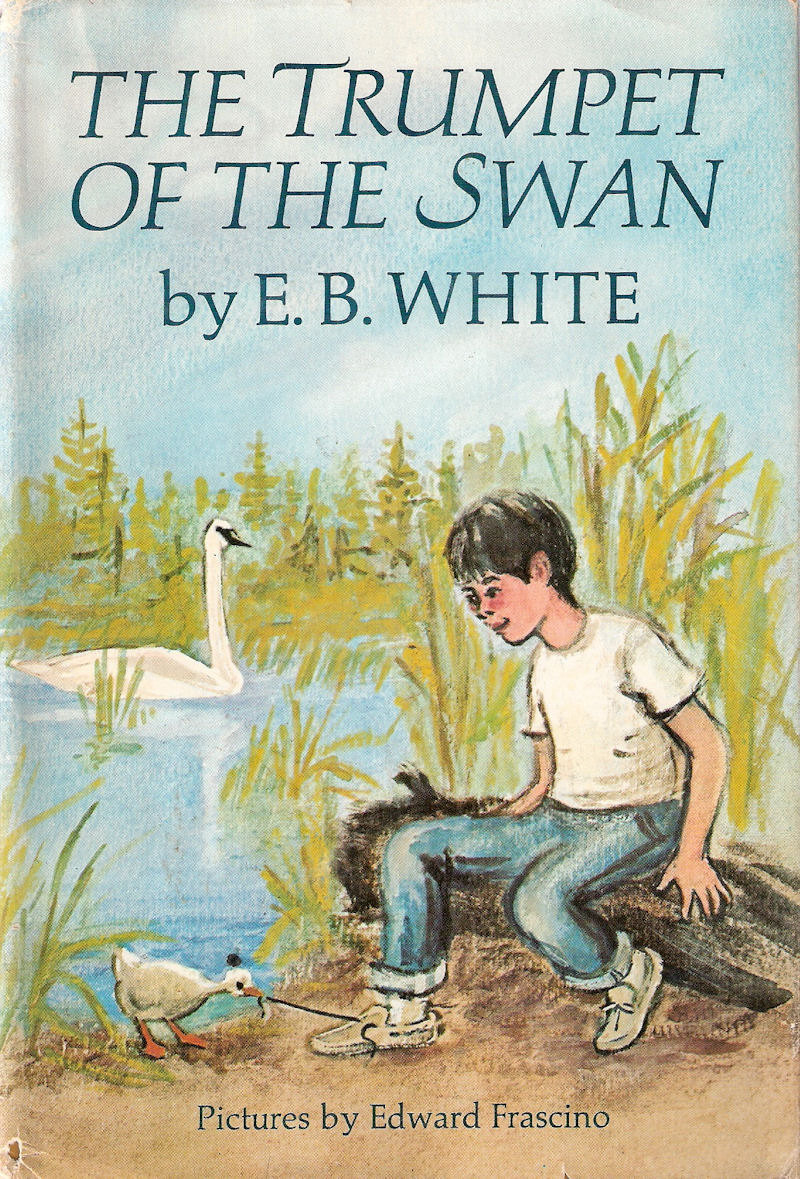

We've included example summaries of each part from The Trumpet of the Swan by E.B. White, along with images from our workshop activities. But of course you and your kids can come up with summaries from the book you're reading. If we offer LitWits Printables for that book, the set includes an interactive worksheet that does that for you—check our 50+ titles.

Explaining each section

1. EXPOSITION: The first look at who’s here, where we are, and what’s going on.

The story’s opening is where we get our bearings, just as we do at the theater when the stage curtain pulls back in Act One. Certain words and images help us quickly understand what time period, location, situation, and people are involved.

Example: Eleven-year-old Sam Beaver, camping with his father in western Canada, journals about having just seen the nest of two Trumpeter swans. He soon returns to watch them from a respectful distance. The swans learn to trust him, especially after he saves the nest from a fox.

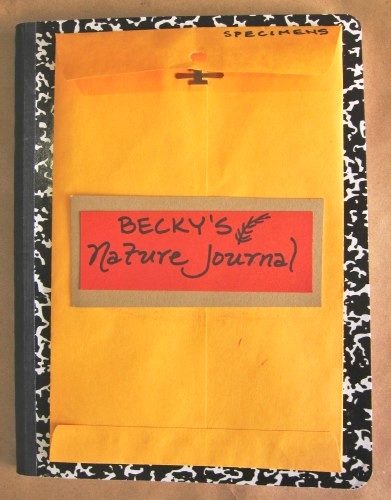

(In our workshop, we paused here to recreate the nature journal, and wrote in it.)

Once we get a sense of the setting and characters, we start wondering "so what?"

2. CONFLICT: The first moment you know what the protagonist (main character) needs most.

This is usually a character lesson that needs to be learned; the “outside” story is just a setup to show us this “inside” problem. If the protagonist seems pretty perfect already, there will be difficulties that put all that goodness to the test, to make him or her even stronger.

Example: One of the hatched cygnets, Louis, is unable to make any sound—he has no voice.

(In our workshop, we paused here to have "swans" communicate vital info and warnings through voiceless charades.)

Once we know what the protagonist is struggling with, we can't wait to see what happens next, and how s/he deals with the problem.

3. RISING ACTION: The ways the protagonist deals with that need for most of the story. As the plot progresses and the protagonist struggles with more difficult situations, the lesson s/he needs to learn becomes more obvious. As a result, the story gets lots more interesting.

Example: Louis's concerned father explains that Louis can’t speak, and the cygnet is frightened and upset. Just a few days after the swan family arrives in Montana, Louis decides to go find Sam there. He learns to read and write and falls in love with the beautiful Serena. The cob steals a trumpet to give his son a voice. Louis earns money playing music at Camp Kookooskoos in Ontario (where he also saves a drowning boy), at the Boston Public Garden, and at a nightclub in Philadelphia.

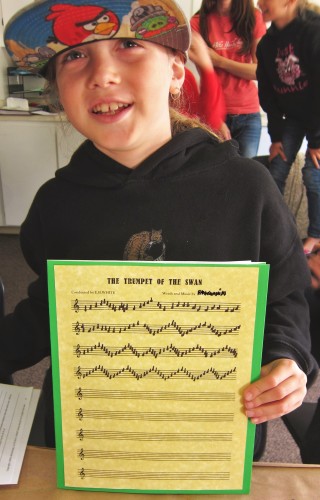

(In our workshop, we paused here to write music and make Camp Kookooskoos t-shirts.)

After a storm, Serena arrives at the Philadelphia Zoo, where Louis is staying. Thanks to his beautiful trumpeting, she falls in love with him.

(In our workshop, we paused here to recreate their room service meal at The Ritz Hotel.)

If things have been getting worse OR seem too good to last, we know something’s going to blow. Sure enough, there’s a crisis moment ahead!

4. CLIMAX: The worst thing that could happen to the protagonist is happening right now!

This is the moment when the story’s action and the protagonist’s problem collide. To fix the situational problem, s/he’ll have to conquer that problem at the same time—alone!

Example: Two zoo keepers sneak up on Serena to clip her wings and keep her at the zoo forever!

(In our workshop, we paused here to discover the theme of finding and using one's voice.)

Once our protagonist is truly stuck, we’re on the edge of our seats! We hope s/he can rise to the occasion and save the day, but we're not absolutely sure.

5. RESOLUTION: How the Conflict is proven fixed, once and for all.

The way the protagonist resolves that crisis in the moment, alone, proves s/he has what it takes to resolve the main Conflict, too.

Example: Louis chases off the men, then uses his slate to argue with zoo management for Serena’s freedom. The Head Man agrees to put off the wing-clipping until after Christmas, and to help Louis send a telegram. Louis wires Sam for help, and offers to pay his plane fare.

(In our workshop, we paused here to consider all the ways that Louis has found his voice, by donning and discussing the item's he's collected. It's a heavy load, which also helps kids feel how hard Louis worked to earn and use that voice.)

Wow, we’re so relieved! Not only did s/he save the day, but s/he did it in ways that prove s/he's conquered the original Conflict. That's the happy ending we wanted for the protagonist—and for us. Because deep down we realize that if s/he could resolve that big “inside” problem, so can we, whether it's anger or loneliness or impatience or having no voice. Now we can relax and turn our attention to less important unresolved issues in the story.

6. FALLING ACTION: How all the loose ends get wrapped up.

The last part of the story makes sure all the characters get what they need or deserve.

Example: Louis and Serena fly back to Montana, the cob pays the store for the stolen trumpet, and Louis and Serena have cygnets of their own year after year. When Sam is twenty and camping with his dad in Canada, he hears Louis playing taps.

(In our workshop, we paused here to track Louis's travels on a map worksheet.)

That's the end of the story! We don’t want to keep reading once everything’s fixed; “happily ever after” is boring. (That’s why the arc is lopsided.) We can put the book down now, satisfied that all is well in that world—and that all can be well in our “real” world, too.

The Core of the Arc

This idea that "if s/he can, so can you" is a vital message of the narrative arc, and of everything we're about at LitWits. If great books do nothing more than teach our kids coping and life skills, they're well worth reading. And we all know they do lots more than that!

We hope this was helpful for you! Here's a printable version of this post. If you'd like detailed explanations of how to help your kids find and summarize each part of the arc, stay tuned for future posts in this series.

Have fun helping kids get life lessons (and more) from great books! Please help yourself to our

Becky & Jenny