Priceless Truths and Pricey Progress in Homer Price

by Jenny

Robert McCloskey's 1943 Homer Price is a laugh-out-loud collection of six stories about small-town life in 1940s America. Its protagonist, Homer, is a nine-year-old boy who's polite, helpful, and smart, and super solution-oriented. As all that, he's always the hero. He single-handedly (well, with the help of four paws and two scent glands 🦨) catches a gang of robbers, helps a superhero out of a ditch, sells thousands of doughnuts in a day to help others, and more. There's a lot of humor, and some tongue-in-cheek lessons about the mixed blessings of ingenuity—we had a blast bringing this book to life in our workshop. But these seemingly silly stories aren't just entertainment for kids. Like all children's literature, Homer Price has loads of wisdom for adults.

We'd chosen to teach Homer Price as a fun, goofy balance to the three more serious, reality-based books we'd just workshopped: The Birchbark House, Little House in the Big Woods, and Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. But those great historical novels were still fresh in our minds, which made little things in Homer Price jump out as important. And not just important in the way that old books sometimes hold bad things up to the light, but important as an example of making good, strong points in clever, indirect, high-impact ways. Ways that make you put on your critical thinking hat and wonder, did he mean it that way?

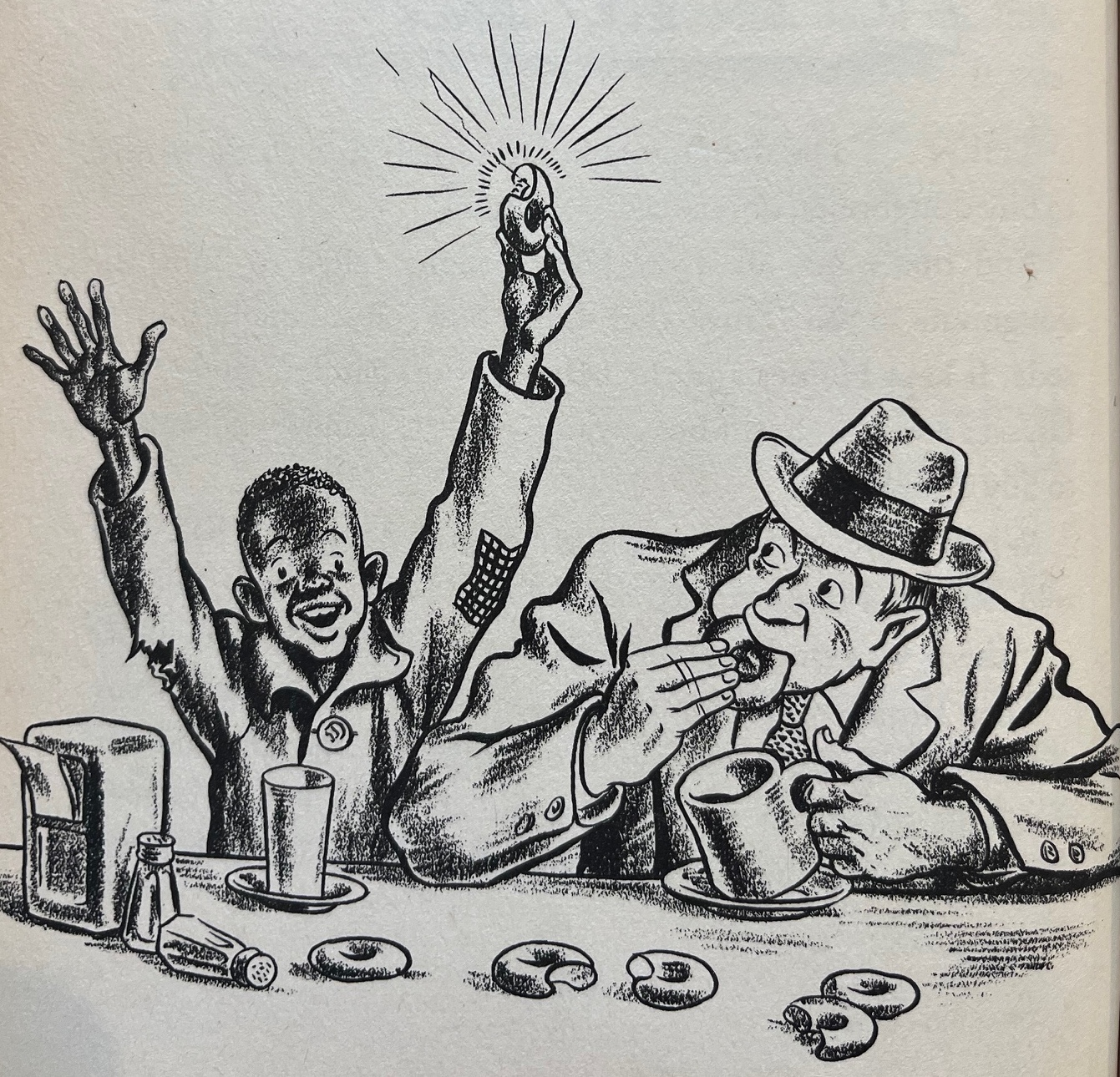

For instance, it may seem at first glance, as it did to us, that the illustration of little Rupert Black, who finds the diamond bracelet in the doughnut, is a caricature of a poor Black child because his clothes aren't in great shape. And that may be so. But the fact that he's sitting at a lunch counter in 1940s Ohio, right next to an unperturbed white man, says a great deal about what Robert McCloskey believed, long before the Greensboro Sit-in of 1960: that a Black child belonged at that counter as much as anyone else, and was just as deserving (if not more) of winning the $100 prize.

From "The Doughnuts" in Homer Price (1943) - book and Illustrations by Robert McCloskey

But the biggest chance to misread McCloskey's views on race is at the end, during the pageant featuring "One Hundred and Fifty Years of Centerburg Progress." Before we go there, keep in mind that in all six stories, the author has gently poked fun at the mixed blessings of technical ingenuity and social progress. He has us laughing at the doughnut machine that goes haywire, and at the shaky foundations of our celebrity "heroes," and with the clever woman who outwits her suitors to make her own choices—he even has a judge speak up for women's rights. In the story "The Wheels of Progress," about pop-up assembly-line houses, he shows the upside of speed and affordable homes, but the downsides of homogeneity and mass production, too—all evident through dialogue and humor. There's even a nod to environmentalism: "Just think," marvels the town's benefactress. "Last week there were only grass and trees and squirrels on this spot!"

In short, McCloskey shows us throughout that progress has its merits—and its price.

Nowhere is that more obvious than in the book's grand finale, the pageant, where Homer and his friends play the parts of Indians in powdered cocoa, striped with mercurochrome, and draped with towel loincloths—truly a caricature. But reading on, it seems meant to make us see the very wrongness of that. During the pageant, to retell Centerburg's "history," the Indians sell 2000 acres of their homeland to the town's founder for a jug of his special Cough Syrup, a blatantly unfair price. When they become addicted to it and rise up, their uprising is quelled "and once more peace and prosperity" reign—for the whites, that is.

The scene is so ludicrous that it can only be satire. Could the point be any clearer that the settlers robbed the Indians of their land, and exposed them to substances (and diseases) that led to addiction and decline? (Alcohol was the primary substance used, but cough syrup makes a good symbol for that, as in those days it contained alcohol and/or opioids.) And can there be any doubt this point isn't limited to fictional Centerburg?

Flash-forward 75 years, and the white Centerburgians are onstage as Spirits of Progress: the Spirit of Water Power, the Spirit of Cough Syrup and Vitamin B Compound, the Spirits of Agriculture, and the Spirit of Progress and Up and Comingness. And all the while, during the whole pageant, the African Baptist Choir is singing music their organist has composed for the event—a remarkable collaboration for the early 1940s.

Beneath the lighter commentaries on the mixed blessings of ingenuity, and the "problem" of an overabundance of doughnuts, I see a bigger story in Homer Price, all summed up in the history pageant. It's a tale of so-called progress based on stolen land and labor, with a soundtrack by descendants of Black people whose lives were traded for America's profit. I see McCloskey writing with an eyebrow raised, so utterly aware of the irony of what was bought, and which cultures paid the most—at what Price America acquired land and Homes.