Help yourself to our creative, hands-on activity ideas for teaching The Birchbark House. We've been teaching children's literature in experiential ways since 2010, and we'd love to help you engage and inspire YOUR kids!

It's astounding how much they'll learn while they're "just" having fun!

When kids get to do things the characters did, they GET IT. With a little guidance, they know why that experience matters. They understand its role in the story, and what secret meaning it has. They see that literature is clever and cool. They get how fun great books are—and they want to read more.

Read on for:

Creative Teaching Ideas

Prep Tips & Printables

FAQ & Support

Learning Links

Our activities are perfect for homeschoolers, co-ops, classrooms, libraries, book clubs, and families.

for use with some of the activity ideas on this page

for teaching The Birchbark House by Louise Erdrich

LitWits makes a small commission (at no extra cost to you) on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

Creative Teaching Idea #1

A table of objects pulled “straight from the story” can lead to all sorts of wonderful discussions and wide-eyed, “aha!” moments. Throughout your teaching experience of this book, pause to discuss and/or pass around relevant props. Items unique to the setting help kids understand “what that was like,” and those symbolic of themes help kids literally grasp big ideas.

The baby's] new makazins were carefully sewn. —Ch. 1

[The young crow gazed up at her with such a calm trusting curiosity that it almost seemed to speak aloud. —Ch. 4

First thing Deydey noticed was the corn—how tall it had grown and how the rain had plumped up the ears. —Ch. 4 | deep in the food cache...Mama set eight birchbark cones of maple sugar. —Ch. 7 | For Mama a precious dress length of calico cloth., -Ch. 4

Chess set and beads

The chess set was always reverently kept in its own blanket... wrapped in red cloth —Ch. 11 | ...there was a tiny sack of all colors of ...seed beads shining and gleaming against the cloth. —Ch. 9

Raccoon and woven rug/blanket

Mama came running to find a curious raccoon trying to steal...fish and venison -Ch. 5 | [The men] made themselves comfortable sitting on blankets on the ground.” -Ch. 5

Birchbark

It was the spring - time to cut the birchbark -Ch. 1

Feathers

[She] was afraid that he would be taken for a wild bird and shot or killed (feathers representing birds as food source) -Ch. 1

![“[She] was afraid that he would be taken for a wild bird and shot or killed” (feathers representing birds as food source) -Ch. 1 - story prop from THE BIRCHBARK HOUSE by Louise Erdrich](https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/content.podia.com/gzam6tp8pfu37g8pukvlc7u1128l)

"Furs"

Once [Mikwam] stopped gathering and selling the furs of of the other Anishinabeg he would go out on his own trapline. -Ch. 5

![“Once [Mikwam] stopped gathering and selling the furs of of the other Anishinabeg he would go out on his own trapline.” -Ch. 5 - story prop from THET BIRCHBARK HOUSE by Louise Erdrich](https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/content.podia.com/snv7h2c1z6mmdpxpednzinfp0dd9)

Thimbles

Her mother came home with...six thimbles for which she'd traded a load of dried fish. -Ch. 3

Creative Teaching Idea #2

We think it's important to know where your books have come from. After all, without the author, we wouldn't have The Birchbark House! This activity introduces your kids to Louise Erdrich through our short video, and lets them practice some note-taking, too.

Photo: Dawn Villella | Associated Press 2013

Start your experience of this story by introducing the kids to the author, so kids can see the connections between her lived story and her written story.

Below is our kid-friendly biography of Louise Erdrich—it's a great discussion starter. If you'd like a worksheet for author note-taking and conversation-starting, there's one in our printables set.

Creative Teaching Idea #3

Chapter 1

Moningwanaykaning is more fun to say than Madeline Island—and knowing its original name honors its original inhabitants. In this activity, kids practice its pronunciation, find key story locations on a map, and learn contextual history, too.

The Birchbark House begins on Spirit Island in Lake Superior, when Omakayas is a baby. But she grows up on Moningwanaykaning, Island of the Golden-Breasted Woodpecker (otherwise known as a flicker). It's known today as Madeline Island. It’s in Chequamegon Bay, just off the northern tip of Wisconsin.

First, have the kids practice pronouncing the island's original name. (As Louise Erdrich explains in her Author's Note, Ojibwa spellings vary based on dialects, phonetic translations, and the way the word is being used. Here and on our geography and history worksheet, we've spelled it the way she does in The Birchbark House.)

Have your kids jot down notes as you share the location— pull back to view in context, then view the island up close—and talk about its history.

If you'd like our geography and history worksheet, it's in our printables set.

TALKING POINTS

According to Ojibwe history and traditions, the Ojibwe were the first inhabitants of Moningwunakauningin. The first Europeans in Wisconsin were two French fur traders, who lived in a hut on the west shore of the bay around 1660. Later, more French built a fort called La Pointe on the island, and it became an important outpost for French, British and American fur traders. In the story, Omakayas and her family live in a cedar cabin at the edge of La Pointe.

Here's a 1-minute video from the Wisconsin Historical Society showing some places and objects of the period, including the 1835 trading station:

The Ojibwe leader Ke-che-waish-ke (Great Renewer), also known as Chief Buffalo, Peezhickee or Bishiki, was born at La Pointe in 1759. He led the Lake Superior Ojibwe into treaties with the United States from 1825 until 1854, and successfully worked to keep the government from removing his people from the region. He is considered a hero of the Lake Superior Ojibwe (also known as the Chippewa).

This video shares some key points about Chief Buffalo, though the primary photo of him may not be of that great man.

Creative Teaching Idea #4

Chapter 1

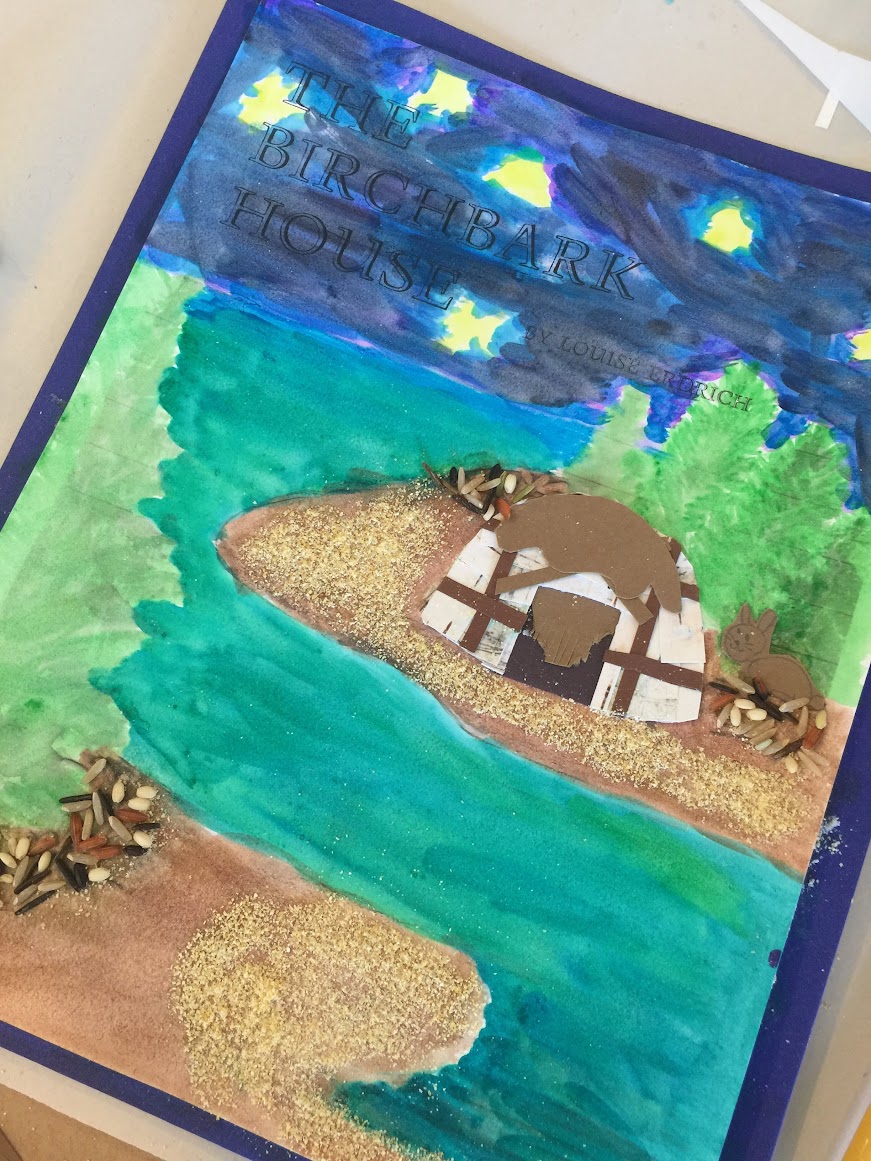

Create your own birchbark homes, perched along sandy shores of cornmeal amid pebbles of wild rice. These natural resources were so important to the diet and tradition of the Ojibwa people, and to the story as well. This activity gives kids a SENSE (or two) of Omakayas's world, and leads to a rich discussion about her culture.

SETUP

Before starting, briefly share the history of Madeline Island, which is named for the daughter of Chief White Crane. Her birth name was Ikwesewe, but when she married the fur trader Michael Cadotte she converted to Catholicism, and her "saint name" became Madeleine. (Just a few of many "blends" in and behind this story!) The Ojibwa had lived on the island long before French explorers arrived in the 1600s. Then the Jesuits arrived in the 1660s, and established a mission at LaPointe, which became an important outpost for French, British and American fur traders.

Take your kids on an online tour of the island's beautiful shorelines, oooh-ing and ahhh-ing over its emerald and royal blue waters, pristine shores, and unique rock formations. If you discuss the colors and textures, and beautiful leaf and stone patterns, the island itself is a lesson in art appreciation.

Take some time to learn about the unique construction and engineering that makes a birchbark house safe and weatherproof, and why it was the perfect summer shelter for a people who were able to take their materials straight from the land.

SUPPLIES

If you'd like to glue this project to a pocket folderfor storing worksheets, add pocket folders to the list.

scissors and glue

1/8” x 2” "saplings" roughly cut from dark brown card stock or construction paper – 4 per

dark brown paper cut into 1 ½ ” or so squares- 1 per

small portions of uncooked cornmeal and wild rice for textural embellishments

Madeline Island shore template (draw your own or use the one in our printables set) printed on card stock – 1 per

birchbark house templates (make your own or use the one in our printables set) printed on plain paper – 1 house per

birchbark patterns (find images online or use the one in our printables) printed on card stock, cut into ¾” (or so) strips – 2 strips per

DIRECTIONS

Hand out the template and watercolor supplies.

1. Use watercolors to add the water, sky and foliage to the background template.

Tell the kids that they’ll construct their houses while the paint is drying, then add textures at the end. While they're painting, play some Ojibwa music. You might want to use this time to talk about smallpox, Native American perspectives on land ownership, favorite scenes in the story, or any other topics you choose. (See our Learning Links at the bottom of this page for lots of ideas.)

2. Cut out the house template.

Before beginning the birchbark house “construction,” show this page about how birchbark homes are made, and share photos of birchbark houses. Talk about what makes a birchbark house weatherproof, comfortable, and functional.

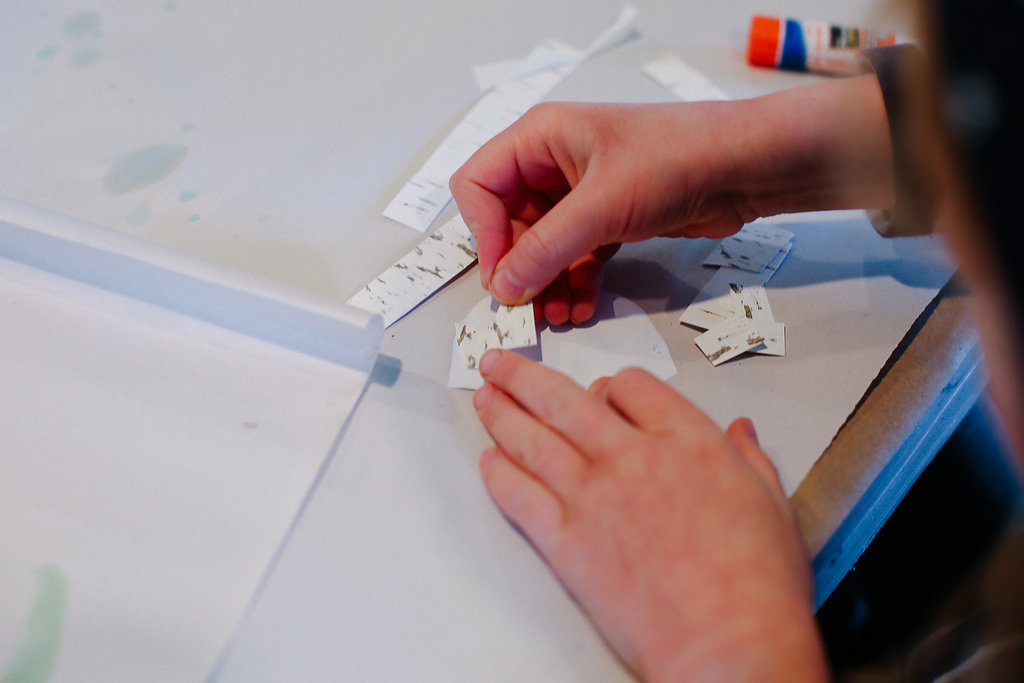

3. Cut the “birchbark” strips into rectangles, then glue them to the houses. Start with the bottom row first so you can overlap the next rows above (to keep out the rain). The pieces can be glued on rather willy-nilly, then you can trim off the excess around the outside edges and the doorway.

4. Finish the wigwam with strips of “saplings,” trimming off the extra like you did for the birchbark. Add dark brown or black paper behind the doorway.

5. Once the paintings are dry, add cornmeal sand and wild rice pebbles/cones to the shores, then glue the completed birchbark house to the scene.

Of course there’s no end to the embellishments your kids can add if they have time—a fire peeking from within the house, animals in the woods, a birchbark canoe on the shore, skins to cover the smokehole and doorway, or whatever they imagine.

DISCUSSION

First, pull up a map and explain that the Ojibwa used to live along the Atlantic, but a prophecy about “food that grows on water” motivated them to move to the Great Lakes region about 1,500 years ago. (Ask the kids what that food might be!) In fact, the Ojibwa call themselves Anishinabeg (Original People), because they believe they’re the ancestors of all North American tribes.

Next, talk tabout the big idea of culture— the collective beliefs, art forms, social rules, and day-to-day operations of a particular group of people. (“Operations” might include what they eat, how they store and serve food, what kind of house they live in, and what they wear.)

Share a few ways the Ojibwa are different from many other Native American tribes:

they invented the dreamcatcher

they make wigwams, canoes, scrolls, and baskets out of birchbark

their moccasins are “puckered” around the toes (Ojibwa means “puckering”)

they have their own language

You can listen to an Ojibwa man speak his language here and read an Ojibwa picture glossary here. If you’d like to teach the kids a few easy Ojibwa words, aaniin (pronounced ah-neen) is a friendly greeting, and miigwech (pronounced mee-gwetch) means “thank you.”

Ask the kids what they learned about Ojibwa culture in The Birchbark House. What makes the Ojibwa people in this story different from the European settlers? You might want to divide the kids into four teams, and ask each team to come up with Beliefs, Art, Rules, or Operations.

There’s lots lots more to learn, of course—browse our Learning Links at the bottom of this page for many more resources.

LitWits makes a small commission on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

Creative Teaching Idea #5

Chapter 1

Imagine an Ojibwa fur trader like Deydey trying to convince two overstocked French shopkeepers (with ridiculous accents) to take his pelts. In this fun activity, kids learn firsthand about bartering, persuasion, supply-and-demand, and the French in Minnesota--lessons they're far more likely to remember later.

Have the kids “earn” their project supplies for the EurOjibwa Barkmark activity (below) by trading “fur pelts” for thimbles and red cording. This fun activity also emphasizes the idea of cooperation and influence between the Europeans and Ojibwa, and adds fodder (or rather, fur) to discussions.

SETUP

Tell the kids they're going to have to head into LaPointe to trade furs for their next project's materials—red cording and thimibles. But first they'll need to understand what it means to trade, that is, to barter for goods. Define the barter system, and talk about the concept of supply-and-demand, so they know what makes a bartered (or bought) item desirable. Point out that some creative persuasion and storytelling skills might come in hand.

DIRECTIONS

Provide your young Ojibwa traders with birchbark and “pelt” scraps, then send them into La Pointe to trade. Tell them that the French shopkeepers there are over-inventoried, so the kids should think up some persuasive “why you gotta have this pelt” stories while patiently standing in line and awaiting their turn. Also warn them that the two ladies are sometimes a little cranky first thing in the morning, and that they mostly speak French.

(Like most things, this activity is extra fun to do with a partner, but you can be the sole proprietor of the shop.)

The kids will LOVE that idea! But the shopkeepers won’t make it easy. When their shop opens to a long line of giggling traders clutching pelts, the annoyed owners must let loose a volley of no no no monsieurs, no mademoiselles! beaucoup furs already!

But, after reluctantly agreeing to hear one pitch at a time, they'll listen with growing interest and (usually) a deal, while murmuring odd French exclamations (lots of oui oui, rendezvous, mon petit, chauffeur, merci beaucoup, chevron, de ja vu, bourgeois, you get the idea).

Most traders will be eager to tell about the species, quality, and origin of their "pelts." Note: If you forbid tales of killing, the kids will get very creative with their stories of where they found their pelts, e.g. from another trader, or from in a box in Grandpa's attic. But certain storytellers (and you know who they are) might ruin breakfast for such genteel ladies.

TALKING POINTS

You can follow this activity by sharing some information about the fur trade in Minnesota.

LitWits makes a small commission on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

Creative Teaching Idea #6

Chapter 2

What better way to celebrate a book about two blended cultures than a bookmark made with a blend of two cultures’ materials? (Say that three times fast!) This birchbark bookmark (now you see why we settled on “barkmark”) puts natural and traded resources to literary use.

This activity also makes some other big ideas tangible. The bookmark’s purpose reminds us how important it was that the Ojibwa learn to read from the “chimookoman,” and what literacy meant for their ability to negotiate treaties and make other advancements. Since writing was also crucial, the kids will inscribe the back with the chimookoman’s funny tracks for waginogan, the Ojibwa word for “birchbark tipi.”

INSPIRATION

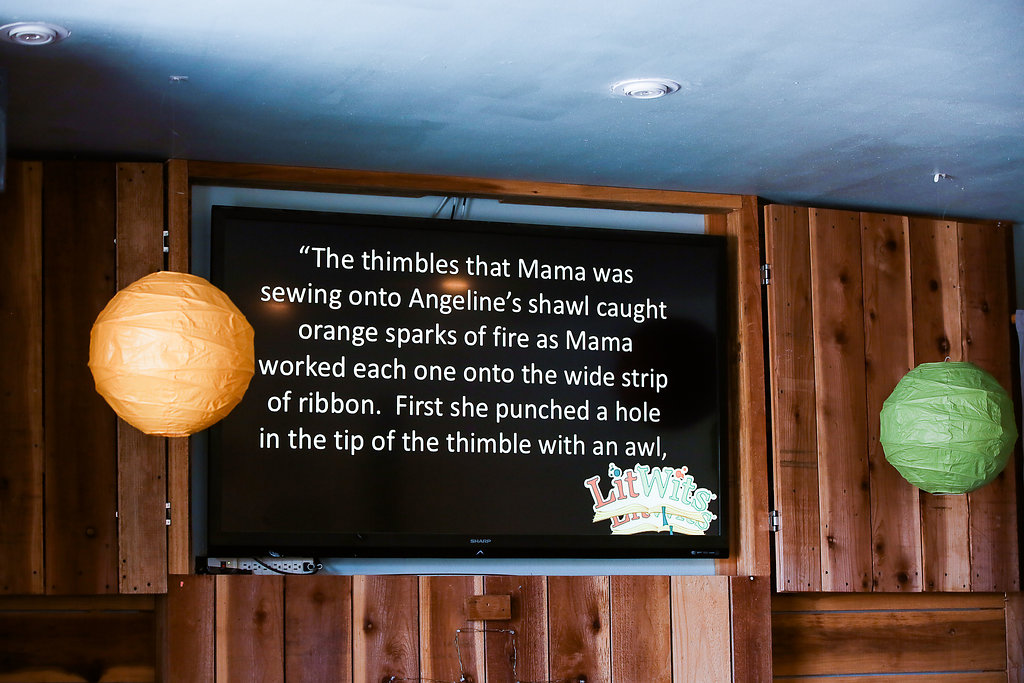

The bookmark’s embellishments are inspired by the way Mama decorated Angelina’s shawl. Mama was a master at creating beautiful handiwork with porcupine quills—she had no need of these funny metal cups to protect her fingers! Rather, she liked the way they looked and sounded hanging in rows from red cords as decorations.

SUPPLIES

See "Trade some fur tales" for a fun way to distribute the thimbles and cording (holding back the other supplies makes the project ahead less obvious, more intriguing.)

birchbark cut into bookmark-sized strips (we used a craft blade) with a hole in one end (we used an awl) – 1/per

8” lengths of 1mm red cord – 1/per

thimbles with a hole in the end (we used an awl, just like Mama) – 1/per

DIRECTIONS

Thread the cord through the thimble and the other rend through the hole in the bark, then knot the cord at each end.

Use a black marker to write the Ojibwa word for birchbark house, waginogan, on the back.

DISCUSSION

As the kids craft, talk about the ways Ojibwa and European cultures both cooperated and collided. This is also a great opportunity to talk about how one culture will appropriate items, skills and knowledge from another, sometimes using them in entirely new or surprising ways.

One of the best examples of this and other kinds of blending is Old Tallow. Read the description of her appearance and traits in the first few pages of Chapter Two, and the description of her coat in Chapter Nine. Just like in our modern culture, clothing is a way we share our feelings and beliefs about ourselves.

Ask the kids to answer the following and to share what their answers make them think about Old Tallow.

Which parts of her outfit and coat are European, and what parts are Ojibwa?

Which items of her clothing were usually worn by women, and which by men?

What two items does she hunt with?

What sharp tool does she share with Omakayas?

In what ways is does she act tough and harsh?

In what ways does she seem soft and kind?

Omakayas’s father gives us another example of blends. Mikwam’s job as a fur trader is closely tied to European settlement; he deals with non-native people all the time, as shown by his clothing and gifts. Review his appearance at the beginning of Chapter Four, and read of the gifts he gives after telling his ghost story. You might want to ask the kids:

What parts of his clothing are Ojibwa?

Of what heritage is his father?

Which of his gifts are made by Europeans, and which are not?

How is his gift to Omakayas a blend of two cultures and uses?

LitWits makes a small commission on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

Creative Teaching Idea #7

Chapter 4

It's always fun for kids to get their fingers in some dirt, and anticipate the growth of of seeds. But this easy, inexpensive planting activity also gets their hands on the theme of "blends" in this book—in this case, the blending of natural and manmade art.

The corn seeds represent the harvest so important for survival, that Omakayas and Angeline defended from the crows in Chapter 4. Decorating the pots with colorful seed beads also creates a chance to show the kids some beautiful beadwork done by the Ojibwa.

Besides those meaningful tie-ins to the story and the Ojibwa culture, most kids love to get their fingers in the dirt, and anticipate the growth of their seeds.

SUPPLIES

small clay or compostable pots

potting soil

Indian corn seeds

beads

glue (drip or stick)

DIRECTIONS

Share images of beadwork done by the Ojibwa, and ask the kids to create a beaded pattern on their pots.

Use stick or drip glue to add beads to the outside of the pot before planting.

LitWits makes a small commission on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

Creative Teaching Idea #8

Know what? Write that. Louise Erdrich wonderfully models the writers' tenet "write what you know" all throughout The Birchbark House. In this prewriting activity, kids learn interesting, important details about the author's life, then put themselves in her shoes as a writer to brainstorm possible subjects of their own.

SETUP

Ask the kids what it means to "write what you know." Point out that it does NOT mean you can't do research and learn new things! It has more to do with writing a story from the heart and personal experience, which is what makes the story more believable and relatable.

The Birchbark House is an excellent example of an author writing "from the inside out," using parts of her own life and feelings as the basis for Omakayas's. Share her background, below, before doing the brainstorming activity.

SUPPLIES

If you'd like to use our creative writing worksheet to help the kids develop their ideas, it's in our printables set.

DISCUSSION

Louise Erdrich (pronounced air-drik) was born in 1954. The eldest of seven children, her parents both taught at a boarding school for Native American children in North Dakota. Her mother was a Chippewa woman of half-Ojibwa, half-French blood, and her grandfather served as tribal chairman to the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians for many years.

How do these real-life facts about her life show up in her book?

Ojibwa culture was a very important part of her life, and this shows in most of the stories, poems and books she’s produced throughout her career. In 2021, she won a Pulitzer for The Night Watchman, about her grandfather's successful fight to keep five tribes from being terminated by federal legislation!

Ms. Erdrich’s parents encouraged her to write from the time she was very young—her father introduced her and her siblings to the works of William Shakespeare, and paid them a nickel apiece for their stories. Her mother made book covers for them out of woven strips of construction paper, stapled together.

Does anything about her parents remind you of Omakayas's parents?

Ms. Erdrich entered the Native American Studies program at Dartmouth College as part of that university’s first co-ed class. She would later marry the program’s director, anthropologist and writer Michael Dorris, and they would go on to write several books together. As newlyweds they earned extra money by publishing romantic fiction under the pen name Milou North – “Mi” from Michael plus “Lou” from Louise + “North” from North Dakota.

Besides writing children’s books, Ms. Erdrich wrote a lot of poetry and many novels for adults. An important theme of her work is the struggles (and blends) between American native and non-native cultures.

Where do these blends, including the struggle between cultures, show up most clearly in The Birchbark House?

Knowing even these few details about the author’s life sheds new light on The Birchbark House, doesn’t it? Ask the kids what other parts of the story Ms. Erdrich may have been writing about from experience. The taste of bannock? The fragrance of kinnikinnick smoke? The sound of traditional stories being told from one generation to the next? All of these would have been part of her world, either as a child or as an adult exploring her cultural heritage.

DIRECTIONS

After you've talked about the author's connections to her story, ask the kids to imagine what might inspire them as writers throughout their lives. It might be a sport culture they love, or a family tradition that’s important to them, or the place they live. Often it’s the things we take most for granted, like family, that end up being the most influential. And it’s often just day-to-day things that provide great fodder: the way breakfast smells when it’s cooking, or the way a favorite uncle puts on his shoes. All of life’s details can work their way into our stories through our experiences.

Have the kids come up with topics they know and care about, and would like to share with others in greater detail someday. (If you'd like to use our creative writing worksheet to help the kids develop their ideas, it's in our printables set.)

If they work with a partner or group, have them read their ideas aloud and ask listeners what stood out—that detail would be the story's "hook."

You can follow up this brainstorming idea with the opportunity to write an story (or essay) that includes some research.

Creative Teaching Idea #9

Chapter 6

Kids love getting a taste of the story—especially if you choose a food that's either unfamiliar or important to a plot point or theme, or all three. For The Birchbark House, we didn't have to invent reasons to include maple sugar. Wisconsin maple sugar and authentic bannock hit all three points.

This straight-from-the-story snack of bannock and maple sugar reminds us of the time Omakayas shared this treat with the bear cubs. (You’ll find the inspiration for this “taste of the story” in Chapter Six.)

We used Wisconsin organic maple sugar and poured it from a birchbark cone, like Mama did in Chapter Eleven. (If you can't find birchbark thin enough to curl into a cone, you could use the birchbark paper for the wigwam activity in our printables set.)

There are various ways to make bannock – here’s the recipe our kids thought was delicious! Of course we added blueberries to the batter and plenty of maple sugar on top, so that might have had something to do with it.

TALKING POINTS

While we ate, we talked about the history of bannock. It used to be made from camas bulbs until European settlers came along with wheat flour and made it even more delicious (and easier to make). It’s now considered a cultural icon associated with indigenous people across the continent.

LitWits makes a small commission on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

Creative Teaching Idea #10

Chapter 6

Wait, whose story IS this? The Birchbark House is mostly told from Omakayas's perspective, but sometimes the author hops from one head to another for a different point of view. "Head-hopping" helps us understand different ways of looking at situations, in books and in life. In this creative writing activity, kids get to try that out in writing.

SETUP

Talk to the kids about perspective. Point out that In this story we mostly know only what Omakayas is experiencing. We know what happens as she sees, hears, smells, tastes, and touches it. We know what she thinks and feels. Once in a while, though, the author lets us in on a different character’s firsthand experiences.

For instance, in Chapter 6, we’re left alone with Pinch and those tempting berries. We’re not just told what he does, but what he’s feeling and thinking. When he tells his mother that Andeg ate the berries, we’re not just told that she throws a stick at the bird, but what she’s feeling and thinking. The author has “hopped” from Omakayas’s mind to her brother’s and then to her mother’s.

DIRECTIONS

Let’s try it! Think about the scene in Chapter 2 when Omakayas is wiggling a leafy stick for the bear cubs, and suddenly the mother bear flips her on her back and pins her down. How would each of these characters describe that exact same scene, in one or two sentences?

SUPPLIES

You can choose the scene and other characters yourself, or use othe creative writing worksheet in our printables set.

Creative Teaching Idea #11

Chapter 10

The Birchbark House is packed with references to "mixing it up." In this vocabulary and writing activity, kids mix some English and Anishinaabemowin words to describe a famous painting of a famous Ojibwe chief.

PREP

Make a list of Anishinaabemowin nouns and verbs with their English translation, and make a copy for each child. (Our vocabulary worksheet, in our printables set, does this for you.)

DIRECTIONS

Explain that the language of the Ojibwe, called Anishinaabemowin, which means “the language of a good person," was an unwritten language until the late 20th century, when its speakers began preserving it by writing it “the way it sounds,” using English letters.

Point out that this blend of Anishinaabemowin sounds and English letters is yet one more example of two cultures blending. Tell them they're going to take that blend and do even more blending!

Ask them to blend English and Anishinaabemowin words to describe a painting of an Ojibwa person or scene, such as this one:

A-wun-ne-wa-be, Bird of Thunder (1845) by George Catlin

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Distribute your list of words, or the "vocabulary writing" worksheet in our printables set, and give the kids time to compose a description in "Anishinaabemowinglish." Invite volunteers to read their work aloud. They'll either be intimidated or enthralled by the chance to try pronouncing new words; if you'd like to expand on this learning opportunity, here's a guide to basic Ojibwa pronunciation.

With older kids, you might want to go on to talk about the portrayal of Indigenous peopls in European art.

Creative Teaching Idea #12

Chapter 9

Order, order! Without it, there's no story—just jumbled miscellaneous parts. This activity kids learn the important concept of the narrative arc (useful for all communications!), and understand how Louise Erdrich intentionally, artfully arranged The Birchbark House.

You can discuss the narrative arc in any of these three ways; we've found the first to be the most engaging, because it breaks up the discussion into bite-size chunks.

Introduce the concept of the narrative arc up front, but save the story's scenes to discuss as you go, pausing to "do what the characters did" in fun hands-on ways, while weaving in discussions and other worksheets.

OR introduce the concept and complete the worksheet before the activities, so kids have a review of the story fresh in their heads first, and you can remind them "where we are" on the arc as you go.

OR at the end of your activities, introduce the concept, then help kids figure out where the different parts of this story fit on it.

The narrative arc worksheet in our printables set summarizes the story by plot point, and has kids fill in some blanks.

Creative Teaching Idea #13

We all love collecting souvenirs that remind us of remarkable places we've been. Give your kids a travel sticker commemorating their literary journey through The Birchbark House, and your field trip inside the book!

Give the kids the souvenir travel sticker included in our printables set, or have them design their own.

Kids might like to add their sticker to a reading kit, like an old briefcase (or faux vintage) or a suitcase that can hold a book, bookmark, glasses, snack, blanket, journal, pen, and whatever!

Or they might want to put it on a binder or water bottle. No matter where they see their sticker later, it will remind them of this wonderful journey they've taken with you!

LitWits makes a small commission on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

Some of our activity ideas need printables or worksheets. Don't spend hours coming up with your own!

for teaching The Birchbark House by Louise Erdrich

Borrow or buyThe Birchbark House, if you don't already have it. You can also listen to an audio version, read by the author. Reading on a screen should be a last resort. The sensory feel of the pages in your hand, or the sound of someone reading to you, is the first important step in sinking into the sensory experience of this story.

The Birchbark House is best for ages 8-12. (You can read reviews on Amazon). Here's our short summary of the story:

Omakayas is a seven-year-old Ojibwa girl, the only survivor of a smallpox epidemic on an island in Lake Superior. Adopted and raised on another island, she gives us a child’s-eye view of Ojibwa life, culture, and skills. We’re right there with her for four seasons as she builds The Birchbark House, harvests rice, befriends bears, tans hides, picks berries, moves into the cedar log house, and collects maple sugar—and discovers her own unique talent and role in the world. .

This 1999 book is an excellent companion to Little House in the Big Woods, which is told from a young girl's perspective as a white settler. Louise Erdrich's rich, thoughtful story of a young Ojibwa girl, set in nearly the same time and place as Little House, adds some balance through voices not heard in that book.

LitWits makes a small commission on supplies or books you buy through our Amazon affiliate links.

You can have them read or listen to The Birchbark House on their own, or you can enjoy it together as a class. Most importantly, read only for fun! Tell the kids to simply enjoy the book, without any assignments in mind. It's hard to get caught up in a story if you're supposed to be looking for something that takes you out of it.

It's helpful to know this book's big teaching points ahead of time, and explore some fascinating links to add to your lessons. We already found those for you, so you too could enjoy reading the book without an assignment in mind. :) Our teaching ideas connect to these takeaway topics:

Ojibwa Culture

This story teaches so much about the Ojibwa culture, without being “teachy!” Omakayas herself, through her words and actions, shows us what she eats, and how her family stores and serves food, and what kind of house they live in, and what they wear, and how they play, and much more. In our workshop, we were able to tangibly represent or engage with many of those elements, making the cultural concepts sensory and real. We added a few more fascinating facts, along with some language and history, to help our kids grasp the specialness of the Ojibwa tribe.

Tell Your Story

Great authors write what they know and care about, as Louise Erdrich does so well. She’s a descendent of people who lived on Madeline Island at the time in which this book was set—in fact, this book incorporates much of her family’s story. Old Wild Rice is actually one of her ancestors! Through her book, kids learn that "writing what you know" makes a story easier to write, but "writing what matters to you" gives your knowledge a purpose and your story more power to influence.

Blends

This story is full of things and people that represent blends—most notably, the blend of Ojibwa and European elements. (The two cultures were introduced in the 1600s, when French priests, explorers, and then fur traders arrived at Lake Superior.) Other blends in this story are intangible—Omakayas’s mixed reaction to her father’s gift, and her mixed feelings for Pinch, and her mixed feelings about Andeg when he flies away—and those are all feelings with which any kids of any culture and time can identify. Just as in real life, characters in great books are complex, complicated, and sometimes downright difficult. And like alloys, blends are what make people strong and interesting—as we see in Omakayas, her father, and Old Tallow.

Additional topics

You might want to explore the supportive Learning Links at the end of this page, especially if you have older or more advanced kids. Make notes as you go, so you’ll remember what you want to share, and when.

Once you've read The Birchbark House and have a feel for its big ideas, decide which activities to do. Don't feel you need to do them all! Choose one or two or whatever you think will best suit you and your kids. Having said that, here's a sample agenda for a 3-hour "field trip" through a great book.

This sample agenda can be followed in part or in whole, all at once or over weeks—whatever works for you.

Set the tone. Ask the kids how this book made them feel, and why, and what it made them want to do. Point out that the author intended to make readers feel, think, and act—that literature is never just entertainment.

Introduce the author. Next, introduce the author through the biography video provided, to pay tribute to the story’s creator and recognize how his/her life story shows up in the book.

Introduce the arc. Give a brief overview of the concept of the narrative arc (here's our explanation for kids). Assure the kids you'll go through it in detail together.

Find the setting. Get your bearings before you set off! Explore the setting through audiovisual aids, and talk about any setting-specific props,

GET HANDS-ON ! Do the activities you've chosen (we do them in story order, for the most part, but do whatever holds your kids' interest.) Talk about the meaning(s) embedded in each project. Pass around props at relevant points to give the kids a tactile, sensory engagement with a significant item, including food and sounds. Look for moments to pop in an audiovisual—hear that medieval chant! watch that Friesland horse run!

Worksheets: If you're using our worksheets, we suggest weaving them in between activities, to keep the writing light and energy high. This woven blend of doing, talking, and writing is what helps lessons stick, and makes this book more meaningful and memorable for your kids.

Timing: This means you're doing a new activity every 10-20 minutes, so things move quickly and the energy stays high. Of course, if your kids would benefit from a slower pace, by all means take your time. The point is to keep everyone relaxed and having fun—so they're better able to learn. Do whatever best serves your teaching needs, in the order and at the pace that keeps your kids respectfully, happily engaged.

WRAP IT UP! Once you've gone through the narrative arc, reward everyone with a souvenir travel sticker—you can have the kids make one, or give them the one included in our printables set. It's just a fun way of proving they've been "there and back again."

Gather or buy your supplies. You can right-click anywhere on this page to print lists and instructions, if you'd like a hard copy—you'll need to open up the "Read more" drop-downs first.

Do the activity prep you'd rather handle yourself than have your kids do; this will depend on your time, kids' ages and abilities (and how important it is to you that the finished project looks as intended!).

Print the printables you're using, whether you made them or bought our set. Which brings us to . . .

Don't spend hours creating worksheets and printables to use with our activity ideas. We've already made those for you!

Buy our full set, for just about nothing.

Be sure to let us know how it goes! In fact, if your kids have a blast with this book, we'd love your help spreading the word about our resources for teaching children's literature.

Tag and follow us on Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and Pinterest—and please leave a review!

for teaching The Birchbark House by Louise Erdrich

Aw, you’re just the right age, whatever that might be! Just kidding—we know what you mean. We find that 8-12-year-olds are consistently “ready to LitWit.” Generally speaking, their reading level is high enough to take on the vocabulary and syntax of literature, and they’ve acquired enough knowledge to grasp new ideas. Yet they’re still full of wonder, and are highly responsive to the “check this out!” nature of sensory immersion.

However, we often have mature kids of 6-7 in our experiential workshops, and sometimes fun-loving kids of 13-14. As a teacher or parent, you know best what your kids are ready for and interested in.

Yes. Our methods and ideas are adaptable to a wide range of abilities—kids particpate at their own level. The point isn't to come up with a stellar work of art or a perfectly polished project, but to have the experience of doing something the characters did, or a spin on it. After all, those characters were of mixed abilities, too!

This is true of mixed levels of enthusiasm as well. Kids who already love reading are thrilled to get the chance to extend the story, and kids who don't yet believe that stories are fun end up wanting to read (or listen to) more great books.

LitWitting is a flexible, fun way to teach, adaptable to all ages and abilities, so there isn't "one way to do it" —every educator's circumstances and children are different. Having said that, we suggest you follow the narrative arc, and we've provided an example of a simple plan above, under Prep Tips.

But the truth is, if you and your kids are having fun, and when it's over they want more (which means reading another great book), you’re doing it right!

Absolutely—but when you're finished, they'll probably ask if there's something else you can do, or have a suggestion of their own! And that's GREAT! It shows they're liking this kind of learning, and seeing that books can be experiences for them too, not just for the people in the story.

Get your feet wet with a project you think they'll like best, never mind how deep and meaningful it is—even if they're "over" this book, if they know you'll be LitWitting other books, they'll want to read them!

In our workshops, the very most reluctant readers are the ones who, when their mom comes to pick them up, are tugging at her sleeve and saying "sign me up for the next book they're doing!" (We love that they always say "doing!").

They're right here on this page! Just click the "Read more" under each activity for all the details.

You can right-click to print this page, if you'd like a hard copy—be sure to open all the drop-downs first, so the hidden contents will print too.

We keep all this info online so we can include helpful links, make updates in real time, add new ideas, and let you use our materials on a screen.

Sure you can, for your noncommercial use in your family, classroom, library, book club, or wherever! As long as you’re not calling your fun time a “LitWits” event or charging a fee, you can use our ideas and printables to do lots of wonderful things!

Please don’t forward your printables or make copies for people who haven’t paid for them, of course, out of courtesy and to honor our copyright, and per our Terms of Service.

Did you find what you were looking for? Do you still have a question? Are you feeling inspired, but maybe also somewhat overwhelmed? Never fear—we're glad to help! You're literally on our page about inspiring kids to read more, and we'd love to support you as you change the world, one book at a time.

Happy teaching,

Becky and Jenny

Sisters, best friends, and partners

for teaching The Birchbark House by Louise Erdrich

Like all children's literature, this book is chock-full of many subjects to explore—from the making of maple syrup to the early fur trade to the effects of smallpox on the Ojibwa of Lake Superior. Browse these curated links to supplement your reading experience, research points of interest, and prompt tangential learning opportunities.

Story Supplements

History of the Ojibwe (3-min video) - Native Hope

Madeline Island History - Heritage, MI Art School

Madeline Island History - MI.com

Madeline Island maps - MI.com

Facts for Kids About the Ojibwa – Native Languages of the Americas

Madeline Island webcam – Chamber of Commerce

Smallpox facts for kids - Britannica Kids

History of the Ojibwa at Madeline Island – Wisconsin University

Ojibwe of the Apostle Islands in Lake Superior – US NPS

Waynaboozhoo and the Great Flood” (tale told in the story) – UWO.edu

About the Anishinabe (Ojibwa/Chippewa) for kids – MSU E-Museum

Image of Ho-Chunk (Siouan)) children with smallpox, >1880 – Wisconsin Historical Society

Michigan black bears – Bridge Michigan

About the Ojibwa culture - Countries and their Cultures

Making Ojibwe moccasins (as Omakayas does) – PowWows

Ojibwe moccasins and beadwork – US NPS

Turtle Mountain Reservation history and photos (North Dakota Studies.gov)

DIY Wigwam/Birchbark House Construction

Information about the Ojibwe from Minnesota Historical Society

Information about the fur trade from Minnesota Historical Society

The French in America – Canadian Museum of History

Map of modern Chippewa and Powatomi tribes in US/Canada

Learn Anishinaabemowin (language camp in Manistee, MI + CDs for purchase)

Native Americans in the Great Lakes Region – MSU.edu

European diseases’ impact on Native Americans in Wisconsin (includes Ojibwa-Chippewa tribes) – Wisconsin Historical Society

Comprehensive overview of Ojibwa culture and history – EveryCulture

Ojibwa prayer song (2:45) with photos – YouTube

Educator's Corner - resources from the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission.

About the Book & Author

LitWits video mini-biography of Louise Erdrich

Author's Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2021 - Dartmouth

Bio with links to Erdrich’s poetry – Poetry Foundation

Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians (author’s ancestral tribe)

Discussions of the book – Goodreads

Images of Louise Erdrich

Summary and review of the story – Carol Hurst

National Book Foundation finalist in Young People’s Literature

Understanding Louise Erdrich (purchase) – U of South Carolina Press

Beyond the Book

Douglass Houghton’s 1832 report “Vaccination of the Indians” (specific to post-1824 Chippewa on pp 580-581)

"Chief Buffalo Picture Search: Busted Again" on photo commonly misattributed - Chequamegon History

George Catlin paintings of Ojibwa/Chippewa Indians (early 1800s) – Smithsonian

Damage to Ojibwa wild rice beds (NPR)

Documentary about Ojibwa music – PBS

"Investigating the Smallpox Blanket Controversy" (intentional smallpox infections of Native Americans) - American Society of Microbiology

Smallpox alleged intentional infection of the Ojibwa (aka Chippewa) – History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan (Andrew Blackbird, Ottawa chief’s son who served as an official interpreter for the U.S. government) – Google books pg 9-10

From Native Languages of the Americas:

Pronunciation guide for Ojibwa language

1884 translation of Biblical Christmas story in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwa language)

Native American words (translated) in Longfellow’s famous poem “Hiawatha”

“America the Beautiful” in Ojibwa language

Color words (with pictures) in Ojibwa language

Number words (with countables) in Ojibwa language

Basic vocabulary words in Ojibwa language

Animal words (with pictures) on Ojibwa language

Ojibwa folkloric characters and legends